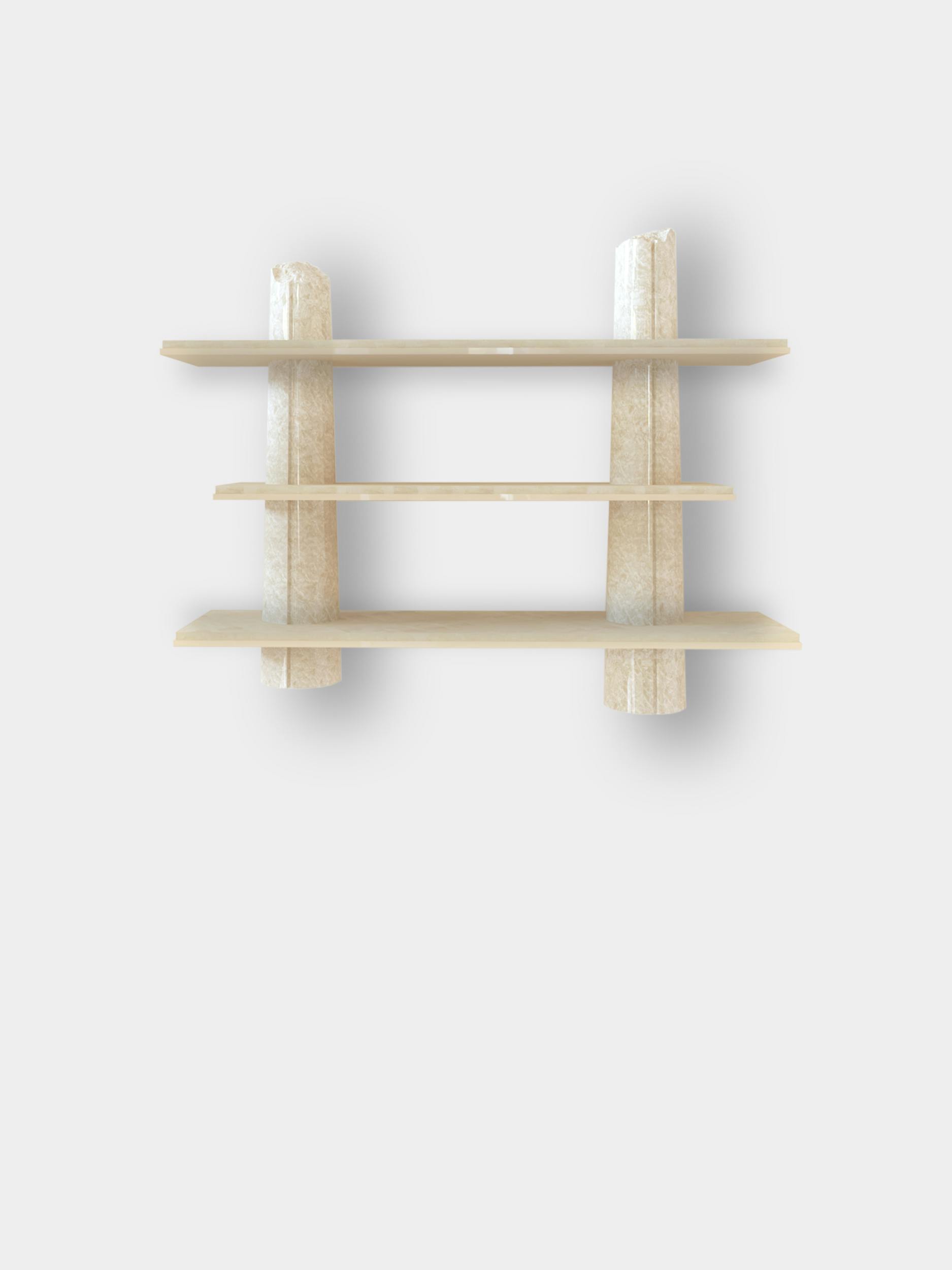

Originally, this material was placed on a table to create a work space and protect the wood from splashed ink. When, during the modern era, the first tables were invented specifically for nobility to use for writing, the word’s usage would change from meaning a temporary workspace to a piece of furniture. It is one of history’s little ironies that it is becoming an increasingly temporary place these days, for other reasons. In the early 17th century, after decades of religious wars, France was at peace. Henry IV was seated on a hard-won throne and society was ready to move on to more sedate activities, a change of pace from the massacres that had plagued the previous century. This was the beginning of an era of unprecedented literary activity, one that persisted through the golden age of French power under Henri IV, Louis XIII, and later Louis XIV. In a kingdom undergoing dramatic centralization, literary salons, preciosity (excessive refinement in art, music, language), and epistolary exchanges fueled the need for a piece of furniture devoted to writing: the desk.

In Memoirs of Maximilian de Bethune, Duke of Sully, Prime Minister to Henry the Great, translated from the original French, Sully tells of when Henry IV insisted on such an object: “…he ordered that I should have a great desk or cabinet, contrived full of drawers and holes, each with a lock and key, and all lined with crimson satin, in such number as to contain, in a regular disposition, all the pieces that were to be there deposited.”The desk spread rapidly for kings and their advisers, nobility, and the upper middle class to use. The early versions were often covered in precious marquetry.