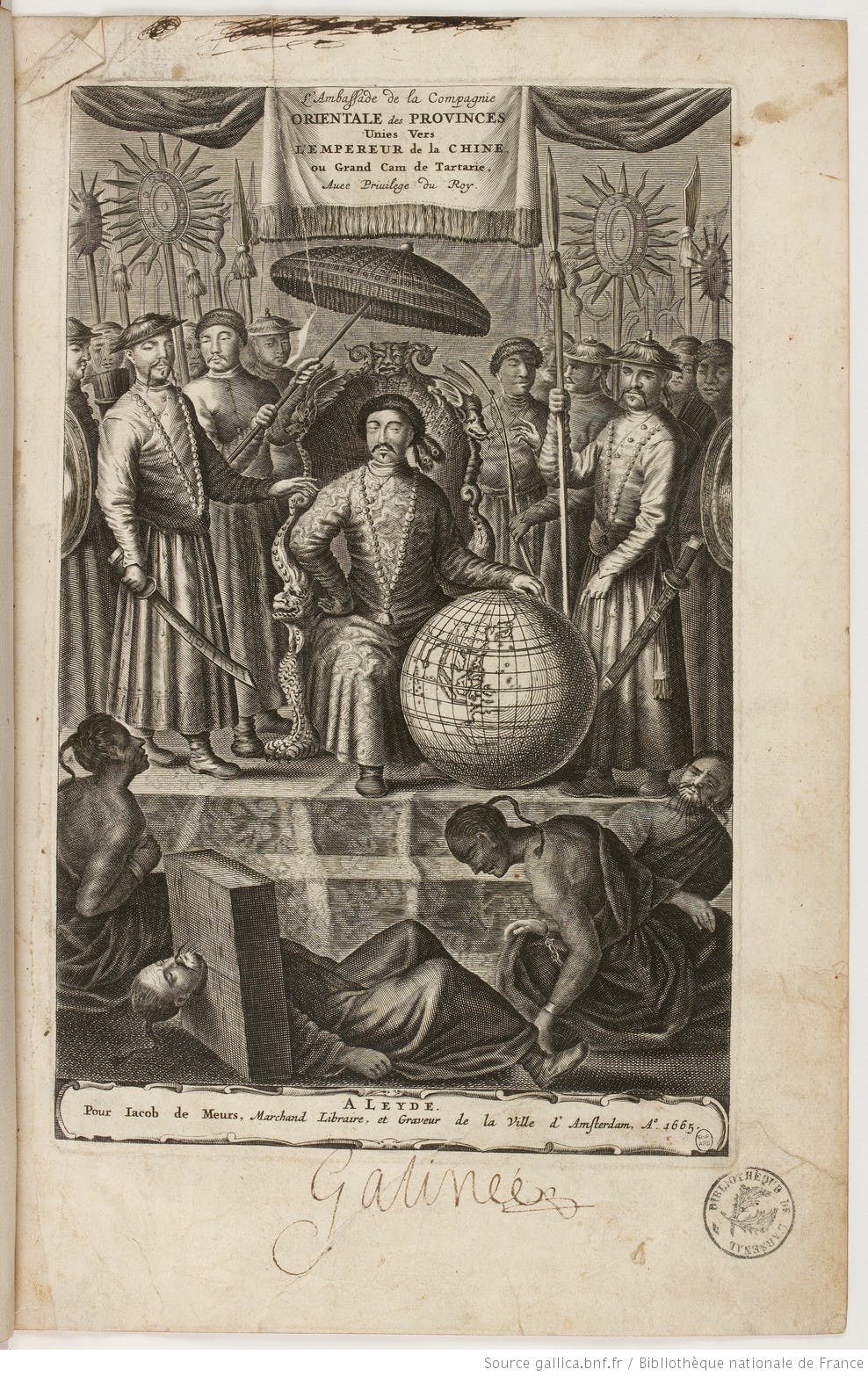

In 1368, while the Hundred Years’ War was still raging in France, five thousand miles away, China’s new Hongwu Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang had ousted the Mongols from power and established the Ming dynasty. Galvanized by the end of foreign dynastic domination, the Middle Empire closed its borders to the rest of the world, with very few exceptions. Seventy years earlier, in 1298, the story of a Venetian merchant in the court of Kublai Khan had sparked tremendous interest in Europe.

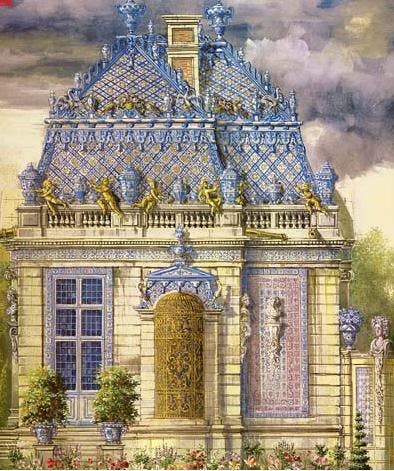

Marco Polo’s Il Milione (Le Devisement du MondeorLivres des Merveilles du Monde in French and commonly known in English as The Travels of Marco Polo) cemented the legend of an immensely rich and exotic China, engendering, as its publication broadened, admiration and astonishment across the continent. Such avid interest could only reinforce the new dynasty’s decision to close the country�’s borders decades later. Who therefore knew what wonderful treasures were hidden within this immense empire ? Ties to the outside world weakened, to be replaced by lore.