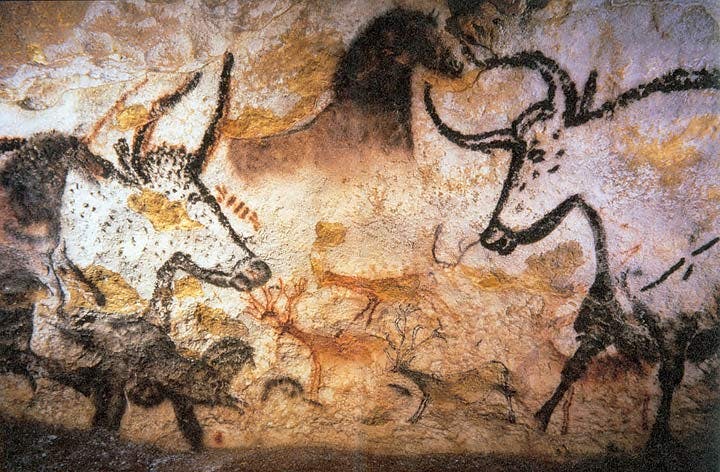

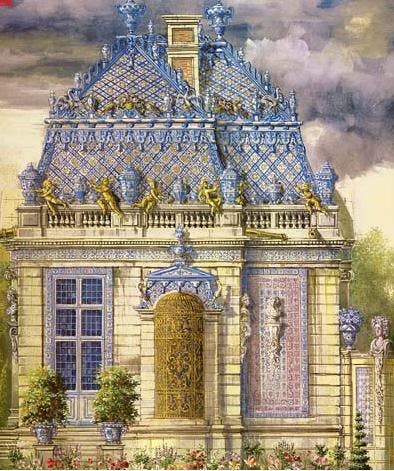

Ornament was a divisive subject in the 20th century, rejected by the modern movement as a sign of decadence, while considered by traditionalists to be a lingua franca uniting the realms of architecture and decoration. This debate has since been pushed aside by architectural post-modernism and contemporary – and deliberately eclectic – interior decoration. Let us look back upon a notion that is as old as humanity itself.